Pratim Ranjan Bose

By all means 2014 was eventful.

The corruption-ridden Manmohan Singh government of Congress-led coalition suffered a humiliating defeat in May. The mandate was not merely against Congress – that had suffered its worst

ever defeat – but, also against the coalition politics.

Frustrated with the prolonged

policy paralysis at the Centre; the young India – cutting across the

religious divide - reposed faith on one of the most controversial characters of

Indian politics. Narendra Modi’s BJP came to

power with a single party majority - a feat last achieved by Congress in 1984 election.

Fair job so far

A fair assessment will tell that

the Modi government hasn’t done badly either, during the last seven months in

office.

At least two major schemes (Swachh Bharat Aviyan and Jan Dhan Yojna ) were rolled out

to address long pending issues in public health and hygiene and, financial

inclusion.

I am sure together they will

impact life of 800 million rural Indians like never before, helping create a

wider and stronger market place.

The task cut out for the new

government was an extremely uphill one on the economic front.

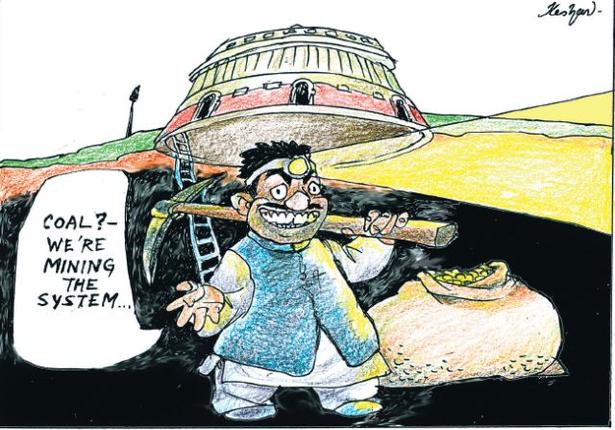

Coal sector –fuelling 72 per cent

of India ’s

electricity demand – was in a mess. Supreme Court cancelled allotment of nearly

200 captive coal blocks. Some 40,000 MW worth of electricity generation

capacities attracting close to $ 33 bn bank finance are either stranded due to

lack of fuel or suffering from low demand.

Gas sector was mired in

controversy on pricing issues. Road, port and rail infrastructure projects were

in jeopardy. Gross irregularities left iron ore sector grasping for breath and

the country was meeting demand through imports. As a spin-off effect, the

banking sector was full with sticky assets.

Having assumed office, Modi

revised the previous government’s decision to double the natural gas prices to

an abnormal high of $8.4 per million metric British thermal unit (mmBtU) . The gas producers are now offered 33 per cent hike to $ 5.61 per mmBtU that

is in sync with the price of imported liquefied natural gas (LNG).

Exercises are on to create

mechanism for distributing the coal assets in a transparent manner as ordered

by the apex court. State owned mining companies were asked to tighten belt and grow

faster to meet demand of either iron ore or coal.

On the policy front, foreign investment limits are raised in insurance sector and the Land Acquisition Act was relaxed to pave way for faster implementation of the infrastructure

projects.

Associated controversies

The initiatives were not free

from controversies either. At least three major decisions involving opening upof the country’s coal sector to private competition;

FDI limit in insurance and amending the Land Acquisition Act; were taken

through ordinances.

An ordinance is a law that is enforced

subject to be ratified by the Parliament at within a stipulated period. The

practice is not recommended unless in urgency. To add fuel to the fire thegovernment re-promulgated some of the ordinances (as in coal) invitingcriticism from the Opposition of indulging in undemocratic practices

While the government blames Opposition for creating roadblock for due discussion on economic issues in the

Parliament; the truth is, BJP should blame its ultra-Hindu nationalist affiliate groups

for diverting attention from the growth agenda.

Buoyed by the electoral success

of Modi; these affiliate groups started indulging in as controversial acts as conversion that doesn't go with the religious fabric of the nation.

While the future will tell how

BJP tackles these groups and ensures rule of law that is most important for

economic growth; it is time for Modi government to take a more level headed

view on the country’s growth prospects in the immediate future, else we may end

up in another set of troubles.

Don’t promise the moon

Looking back the Manmohan Singh

government had run into rough weather by trying to ride the popular aspirations,

way back in 2004-05. In an effort to make the most of the prevailing high

growth regime, the government took a series of hasty decisions be it in

allotting coal blocks, telecom spectrum or setting up power plants.

As they came back for a second

term (2009-14) all of those decisions blew up on their face. Worse, the entire

country paid for such actions.

Modi came to power promising

growth at a time when the world economy was in a topsy-turvy and Indian economy

was in serious trouble.

It was commendable that he started

taking corrective measures to bring the economy back on the rails resulting an

upward revision in projected growth from 4.7% to 5.5% in 2014-15.

But the environment is clearly

not conducive for as high growth, as the government is expecting in 2015-16. The Economist cautioned that the world economy, led by the US, may be heading for tough times in 2015. The Reserve Bank of India

too toed a similar line in its recent financial outlook.

Modi must appreciate that the recent

improvement in India ’s

growth outlook are a result of record drop in crude prices in barely six months.

The credit goes to OPEC’s

decision to run American Shale oil producers out of business by pumping more

crude. But no one knows where OPEC is going to put a stop. No one knows either,

if another war will break out in the West Asia

or some rebels will blow out an oil installation.

The bottomline is, a slight jump

in crude prices will see India

grappling with host of issues – starting from the capital account deficit. And

if the crisis deepens, as in 2008, RBI says the Indian banking sector will not be free from trouble.

We are living in difficult times.

The country will be obliged to Narendra Modi if readies India for

reaping long term benefits. Fueling public expectations on short term gains,

may prove deadly.

***

/pics/164671_logo.jpg)