Pratim Ranjan Bose

(The following is reproduction of my 'introductory comments' during the '10th Foundation Day Lecture' at Jadavpur Association of International Relations on July 20, 2017)

(The following is reproduction of my 'introductory comments' during the '10th Foundation Day Lecture' at Jadavpur Association of International Relations on July 20, 2017)

In 2010, at an International Media Conference in Hong Kong, I had the good opportunity to watch a humorous home video on the life of early American journalists in China. That was during the establishment of formal relations between the two nations, during Jimmy Carter’s presidency, in late 1970’s.

The video had many funny

sidekicks. One scene – shot in slow motion - was particularly humorous. It

showed a Chinese leader spitting in a spittoon on the dais. He was accompanied

by an American leader, who was trying to maintain calm despite signs of serious

discomfort written on his face. The documentary told us, it was a FUNNY act on

the part of the Chinese leader to show his primacy.

To add, the conference

discussed many issues of contemporary importance – starting from business to

politics - in the entire world; except one – there was no mention of any

dissidence in China. I later asked an organiser about this exception. The

answer was straight: the exception was mandatory for the success of the

conference.

But, 1989 was also known for

the Fall of Berlin Wall and a complete shift in economic paradigm towards

globalisation of finance capital and the focus soon shifted to Chinese wonders.

To quote The Economist again: “China was becoming too rich to annoy”. With growth rates, also soared political

arrests (900 in 2008). There were disruptions too, like the Tibet uprising

(2008), Uighur Riot (2009). But they faded to the grandeur of Beijing Olympics

(2008) and China’s $100 billion stimuli that kept the world going during the

Global Financial Crisis. Oslo’s award of the peace prize to Liu Xiaobo’s in

2010 didn’t make much difference. “There are some bored foreigners, with full stomachs, who

have nothing better to do than pointing fingers at us,” Xi Jinping was quoted saying in October 2010.

The Economist now reminds us

that in Xi Jinping’s China, even lawyers are jailed for appearing for people,

arrested on such SERIOUS charges as ‘gathering outside courts during political

trial’ and urged the Western World to speak up for UN resolution for human

rights.

To me, the piece presents a

live case study on “Globalisation, International Relations and Media”. The

issue is not human rights or political freedom in China; but to remind that the

real world was always opportunistic in its application or adherence to moral and

ethical Standards, both before and after globalisation.

India’s tryst with democracy,

with a few hundred dollars per-capita and over 55% people living below poverty

line, didn’t earn favours of the West in 1971, when the US was allying with

Pakistan - where only one elected government survived the term, till date.

The truth- and a sad truth -

is, media was never free from the virtues and vices of global political order.

Loosely speaking, media follows politics. To add to the complexity, media has

its share of perceptions about truth. No one believed that people were

mercilessly killed in East Pakistan till The Sunday Times carried Anthony

Mascarenhas’s article titled “GENOCIDE” in June 1971. Reports in Indian media

about atrocities or migration (to India) didn’t matter.

The global media perception

about India has undergone vast changes since, keeping in tune with the change

in political and economic realities. The Internet has reduced the scope of the

information gap. Yet, perception works. There is no dearth of commentators who

describe India as a FAULTY DEMOCRACY and draws comparisons with China!

China has surely created an

example for growth and prosperity. But, are there many references to a major

country giving universal-franchise a chance - braving abysmal poverty, as India

was in 1947 - and growing with it too?

Having said that the political

blocks of the cold-war era had helped create a pattern in media narrative about

international relation; which is now passé. Globalised era re-emphasised that

END JUSTIFIES THE MEANS, as Deng Xiao Ping was famously quoted saying.

On the international relations

front, it opened exciting opportunities. For example, India is enhancing ties

with a Muslim majority Bangladesh and Israel with the same vigour. But it has

also created scope for moral and ethical dilemmas.

What should be the Indian

approach to the Sheikh Hasina government in Dhaka that is witnessing erosion in

public support? Or, how should the world react to Nobel peace prize winner Ang

San Suu Kyi government on rights abuses in Myanmar vis-a-vis the security

concerns of neighbours? If we can talk about Palestinians or Kashmiris; why did

we forget Chakmas who are hounded and abused in their homeland for last 70

years?

This is exactly media’s

dilemma, in assessing or asserting, its position on international relations.

Media always wanted to meet the gulf between national and global interests. The

new realities narrowed down its choices. Words like “totalitarian” are removed

by “single-party rule”. It can no more take a dogmatic stance for freedom of

speech as it took in 1989. China established that money can rain without it.

Media is on an ethical and moral see-saw. It can neither accept nor deny it. It

can only look forward to global politics to clear the doubts that question the

very existence of media.

And, this is the other reason

why I picked The Economist piece as a case-study. The death of Liu Xiaobo’s has triggered a deluge of reports in global media. But The

Economist was outstanding even to its own standards of covering issues in China

for a decade or so. The share of critical stories – though a gross minority in

number - has surely been rising in global media since China ordered a crackdown

last year. It is a different matter that the extent of criticism was too mellow

from the Indian perspective. The Economist raised the bar.

And, that prompts me to ask

Why? Why it is suddenly occurring to columnists that China doesn’t share good

relations with neighbours, it barely dominates them. Why did we take refuge to

the term Frenemy or “Friendly Enemy” to describe the China-Taiwan relationship

and why we are suddenly spending costly ink on Taiwan’s nervousness about

China? Does it have anything to do with the dramatic, if not dangerous, rise in

militarization in South-China Sea? Is media trying to draw inspiration from the

changing geopolitical landscape in Asia, as is epitomised in OBOR (One-Belt,

One-Road) versus SASEC (South Asian Sub-regional Economic Cooperation) or Asia-Africa

sea link narratives?

If so then, it wouldn’t take

much time for such issues to be trampled by politics, as has always been the

case. Indeed on July 14, CNN came out with a report titled: "The tragedy of

Liu Xiaobo is another victory for China”.

***

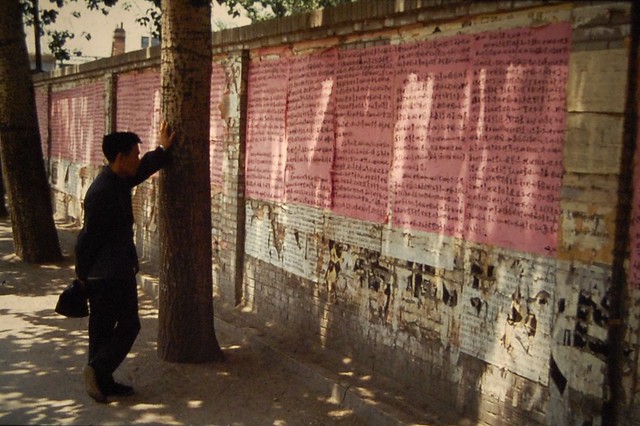

Photo from webTweet:@pratimbose